Pictures of advancing climate change have almost become a part of our daily reality: hurricanes, floods, melting glaciers. Despite the topic receiving regular coverage, it remains an abstract and distant issue for many people. However, the effects of increasing temperatures can no longer be ignored around the world—and Germany is no exception. An inventory of the situation at Hainich National Park.

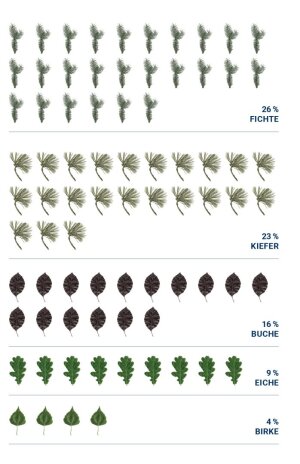

About one third of Germany is covered by forests. The beech is the third most common tree in German forests after the spruce and pine. And similar to spruce and pine trees, beech trees are acutely endangered. The extreme droughts of the last two summers have been especially harmful. The effects of climate change are dramatically visible at Hainich National Park, a 75 km² wooded area in western Thuringia that forms part of the UNESCO World Natural Heritage Site »Ancient and Primeval Beech Forests of the Carpathians and Other Regions of Europe«. A team of researchers at the University of Jena is observing the trees from above. Their images are alarming—vast numbers of beech trees are dying.

Half of the trees are damaged

The extremely dry summers of 2018 and 2019 have left the forest in a precarious condition. »Across vast areas almost half of the trees is damaged or even dead,« says PD Dr Sören Hese. He is sitting in his office at the University’s Institute of Geography and pointing at aerial views of the forest on his monitor. The dense greenness of the treetops is speckled with numerous grey spots (see picture above). »These grey areas are leafless treetops—mainly beeches,« explains Hese.

As part of an ongoing collaborative project with the managers of Hainich National Park and »ThüringenForst«, the earth observation expert and his colleagues from the Department of Earth Observation are examining the woodland in the nature reserve from an aerial perspective. They are using a drone to survey the top of the forest with pinpoint accuracy. The drone weighs around 1.5 kg and has a diameter of 45 cm; it climbs to 100 m and flies along preset areas in a fully automated manner, allowing the researchers to map around 5 km2 of forest per day.

Hainich National Park is the largest continuous area of deciduous woodland in Germany. The southern part is a protected national park, where the trees grow without direct human contact. Hainich National Park is home to an estimated 10,000 animal, plant, and mushroom species. Many deciduous trees flourish in the nutrient-rich shell limestone soil. The most common tree is the European beech.

Image: Liana Franke/FSUThe five most common tree species in German forests. The beech comes in third place as the most common deciduous tree.

Image: Liana Franke

The drone captures thousands of frames during the survey campaigns, which take place regularly between July and November. »The image sections are chosen in such a way that 80% of the area captured by each frame overlaps with the frames taken before and after,« explains Sören Hese. The individual frames are subsequently converted into an overall image. This method also allows the researchers to create detailed, precise elevation models of the treetops, as the drones capture each point from different perspectives and can measure their position in real time.

The photographs captured 2019 paint a dramatic picture. Hese is currently evaluating them to map changes in the forest following the hot summer of 2018. Even outside the hotspots on exposed hillsides, beech trees are dying in great numbers. »Up to 30% of the trees are already dead in several areas,« states Hese. This is confirmed by the latest ground-based reference studies that national park authorities have conducted. It remains to be seen whether partially defoliated trees and those with only a few tiny leaves will recover next year.

Sören Hese stands at the top of the 40-metre Flux Tower at Hainich National Park. This is where the drone is launched.

Image: Sören HeseThe oldest are the first to die

Beeches whose treetops are in the highest area of the forst are under particular threat. These huge trees are around 180 years old, and some are even older. »These older trees are the first to die,« says Hese as he opens an animated elevation model of Hainich National Park generated from 1.2 billion elevation points. The defoliated treetops are easy to spot during the drone flights, as they individual peaks protrude from the canopy below. This problem may primarily be affecting beeches, because they have more superficial roots than other trees, such as oaks, and therefore cannot reach water reserves deep underground.

The survey data not only provides the national park authorities with a comprehensive inventory report; the results are also useful for the remote sensing experts in another way. They can be used as a reference for satellite data to record changes in forest vegetation. »We use data from the ESA earth observation satellites Sentinel-2A and -2B,« explains Hese. The satellites continuously measure the light reflected by the earth and its atmosphere in different wavelength ranges, such as in the infrared and visible range. »We look at time series of these spectral images and use them to detect changes to wooded areas throughout the year,« says Hese. The satellite signal is altered by leaf growth in summer and spring, defoliation in autumn, and the stress of droughts. »However, we can only determine which specific tree changes are responsible for the changes to the satellite signals by comparing drone images and conducting onsite analysis«.

The extent of the changes becomes evident upon closer inspection of the satellite images captured in the summers of 2018 and 2019 at the same time of year (see figure below). The images show a 25 km2 area in the western section of Hainich National Park, presenting satellite data from the short-wave infrared, near-infrared and red spectrum of light. »The differences are significant,« explains Sören Hese. While the wooded areas are primarily green in the false-colour image from 2018, the image captured in 2019 is streaked with large, dark brown patches. These changes are caused by the lack of absorption in the red wavelength range, as the chlorophyll in the dead leaves is no longer active or the leaves are simply missing. The near-infrared range also shows altered reflectivity; this is due to the reduced or missing foliage and the high level of reflection in the near-infrared range that would otherwise be present as a result of intracellular spaces. Finally, absorption is re-duced in the shortwave infrared range, because less water was absorbed than in the summer of 2018 as a result of drought stress.

Lasting changes caused by the hot summers of 2018 and 2019

What does the future hold for beeches at Hainich National Park? This largely depends on how the climate develops over the coming years and whether some of the beech trees can recover over the next twelve months, says Sören Hese. But one thing is for sure: The hot summers of 2018 and 2019 have left a lasting impression on the appearance of Hainich National Park.

By Ute Schönfelder

False-colour satellite imaging of the western section of Hainich National Park from the summers of 2018 (left) and 2019 (right), used to measure the reflection of radiation in infrared and visible red light. The green areas from 2018 are now streaked with dark brown patches in 2019 (in the middle of the image), as caused by the defoliation of the forest.

Image: Sören Hese