Ortolph Fomann the Younger died in 1640 and was buried in the church at the »Collegium Jenense«. Now, almost 400 years later, an interdisciplinary team is working on virtually resurrecting the man who taught history, poetry and law in Jena. The experts involved in the large-scale project are literally examining the bare bones of the professor and his contemporaries to reconstruct their everyday lives at the early modern university. Here they offer insights into their workshops.

By Stephan Laudien

Concentration and a steady hand are some of Gina Grond’s essential tools. She’s wearing nitrile gloves, an FFP3 mask and peering through a large magnifying glass inserted in the middle of a round lamp. The restorer uses a fine brush to carefully spread glue under a layer of paint, then she takes a heated spatula and returns loose flakes of paint to their original position.

Gina Grond is working on a wooden work of art that is roughly the size of a newborn baby. The artwork is a marriage of new life and death, as highlighted by the title on her specification sheet: »Putto mit Totenschädel« (»Putto with Skull«). The carving was part of the epitaph for Ortolph Fomann the Elder, who was a professor in Jena and served as the rector of the university four times between 1595 and 1626. Fomann was buried in the university church (»Kollegienkirche«) on 23 May 1634; the richly embellished epitaph, of which only fragments have been preserved to this day, once reminded posterity of his life and work.

Gina Grond’s desk is housed in a workshop in the depository of the Art Collection at the Friedrich Schiller University Jena: a modest room with white walls and a white ceiling. »It helps us make out different colours,« says Gina Grond. The restorer speaks with respect about the work of art in front of her: »There is its age on the one hand, and the fragility of the material on the other.« The aim of her work is to preserve and conserve the piece. The materials have to be used as reversibly as possible and they have to come close to the originals. As the binding agent contained in the primer and paint has deteriorated significantly over the centuries, Gina Grond is using a type of glue obtained from a sturgeon’s air bladder to refortify the primer and layer of paint. This low-stress glue is well suited to such fine work. Once the primer and paint have been refortified, further technological investigations will be carried out and the surface of the work will be cleaned. As an important aspect of her restoration work, Gina Grond keeps a detailed record for every item, where she meticulously documents the prerestored condition, each stage of her work and the materials used. This will provide future restorers with valuable information for their work. »We’re all part of a chain. We’re not the first to work on the piece—and we certainly won’t be the last,« says Gina Grond.

Around 500 burial sites found on the Kollegienhof grounds

The Kollegienhof project is being coordinated by Dr Enrico Paust. The 35-year-old archaeologist is the curator of the Prehistory and Early History Collection at the University of Jena and he manages the professors’ graves in the Kollegienkirche. The collection includes numerous finds from the Kollegienkirche and the monastery grounds (»Kollegienhof«). The first excavation inside the church took place in 1936, explains Enrico Paust. After the Kollegienkirche had been destroyed by bombs at the end of the Second World War, the site was cleared and further excavations have since followed, most recently in 2019. »Over 500 burial sites were found on the grounds, and over 1,500 people were buried there,« says Enrico Paust, who led the most recent excavation. Most of the graves belonged to noble students, professors and their families. Numerous burial objects were also recovered, including valuable items of clothing such as coats, shoes and wigs.

Enrico Paust’s office in Löbdergraben is just next door to the workshop in which restorer Ivonne Przemuß is examining the burial objects, the items that were given to the deceased on their journey to the afterlife.

Some of the items on her desk include a brush that was presumably used for shaving, washing or powdering, a wooden comb and a wreath-shaped object made of fine, spirally wound wire. »It’s a burial crown,« says Ivonne Przemuß. Such crowns were originally placed on the heads of those who died unmarried in the modern age, so mainly boys and girls who died before coming of age. The crown symbolized their marriage with death. For the restorer, it means a great deal of work! If possible, the metal surface is cleaned with a brush, scalpel and tweezers. Ivonne Przemuß works with a microscope—the fragile pieces demand a high level of concentration. As most of the objects are made from a mixture of materials (metals and organic matter), they have to be well documented and filed, and each material has to be identified. The burial objects feature a seemingly endless range of crafted elements, including gold-coated silver wire and silver-coated copper wire that was shaped into beautiful flowers and leaves, or even real flowers and glass beads. The aim is to precisely document the pieces and, if possible, to conserve them, says Ivonne Przemuß.

One of the most striking items on her desk is a metal object that looks like an oversized piece of jewellery. This curious find, known as a »fonticulus disc«, is mounted on a leather strap. Ivonne Przemuß explains that it was attached to parts of the body such as the upper arm. It was found in the grave belonging to Johann Arnold Friderici, a physician who died in 1672 and had been the rector of the university two years previously. »An incision was made in the body and an object was usually inserted to keep the wound open. The wound was then covered with such a disc and bad fluids were caught by the compress underneath, which has also been recovered«. This patently paradoxical procedure can be explained by the medieval doctrine of four humours, according to which there were four bodily fluids that had to remain in constant equilibrium. If this equilibrium was ever disturbed, bad fluids had to be removed from the body in procedures such as bloodletting. The fonticulus disc discovered in Friderici’s grave shows that the physician was by no means a poor man—the ancient medical device is made of silver.

Indeed, poverty shouldn’t have been an issue for professors in the early modern period. »The magnificent garments recovered from the graves show that the professors were buried in municipal costumes,« states Kim Siebenhüner, Professor of Early Modern History. She points out that their clothing was a status symbol. However, the only material to survive is of animal origin, such as the elaborately embroidered doublet made of precious silk that was found in Friderici’s grave. She explains that historians could help to interpret and classify those finds. »One such question is how the deceased moved from this world to the next,« says Kim Siebenhüner. The professors could have easily been buried in their cap and gown. The Kollegienhof project is also shedding light on further finds, such as the crucifixes recovered from the grounds of the former students’ hostel. What purpose might they have served at a Protestant university? Were they perhaps a sign of the continuity of old orthodox practices? Or are they artefacts from the Dominican monastery that used to occupy the grounds?

Valuable garments are preserved

But let’s get back to Professor Friderici’s doublet. The valuable garment is being processed by Friederike Leibe. The textile restorer works for the State Office for Monument Preservation and Archaeology of Saxony-Anhalt in Halle (Saale). Her weapon of choice is a micro suction device, a pump to which three laboratory glasses are connected. »The textiles recovered from the graves are covered with mould, insect remains and other dirt,« says Friederike Leibe. The aim of her work is to clean and unfold the garments to prepare them for scientific processing. Another aspect of her work revolves around long-term preservation. In this regard, the doublet is in surprisingly good condition—other finds consist of fabric snippets the size of postage stamps and many disintegrate as soon as they are picked up. The doublet was a highly fashionable item of clothing at the time, says Friederike Leibe. The silk probably came from Italy or France and may have been traded at the fair in Leipzig. The restorer has spent a whole 43 days working on the doublet—and her investigations are far from over. For example, the silk velvet may have been dyed with a strong brown dyestuff, but this will have to be confirmed by further detailed analysis. The doublet’s striking selvedges may indicate the area in which the velvet was made. The long list of questions raised by the professor’s doublet are far from answered.

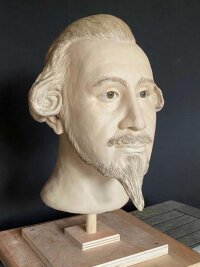

The skulls are given their old face again

Let’s head over to the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the Goethe University Hospital in Frankfurt am Main, where Dr Constanze Niess remodels the faces of the deceased. Facial reconstruction is required whenever human remains are found and the investigating authorities are unable to identify the person. The human skull serves as the basis. »Just like human faces, the proportions of the skull vary considerably from person to person,« says Constanze Niess.

In order to reconstruct the face that once belonged to a skull, Constanze Niess first inserts glass eyes into the eye sockets and then remodels the face layer by layer. She does this using an oil-based modelling clay known as »plasticine«. The advantage of this material is that is doesn’t dry out or tear, but this makes it rather sensitive. The soft tissue is between 0.5 and 1.5 cm thick, but pinpoint accuracy isn’t absolutely essential, says Constanze Niess. »It’s mainly about modelling the person’s characteristic features,« explains the forensic specialist. When pictures of the reconstruction are subsequently released to the public, there is a chance that somebody will recognize the dead person, such as former colleagues, classmates or neighbours.

This method was developed by Mikhail Gerasimov (1907–1970), a Russian anthropologist and sculptor who reconstructed the facial features of historical personalities such as Ivan the Terrible and Friedrich Schiller. His method has since been refined by forensic scientists in the USA and there are now around 100 facial reconstruction experts around the world. Constanze Niess has already reconstructed the countenance of numerous historical personalities, most recently the face of Ortolph Fomann the Younger. The professor of history and poetry died in Jena on 6 June 1640 and was buried in the Kollegienkirche. His face was not modelled on the original skull; instead, Dr Alexander Stößel from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History created a 3D model of the skull that had previously been obtained using a CT scan. His colleagues, Dr Alexander Herbig and Dr Wolfgang Haak, provided information on the professor’s health, eye colour and hair colour, which they had obtained from DNA samples from one of his teeth. If DNA from the Yersinia pestis bacterium is found in a sample, for instance, it is almost certain that the person concerned died as a result of the plague.

Constanze Niess describes her work on Ortolph Fomann as a »great challenge«. After all, she only had a model of the skull to work with. The model was missing parts from the side of the face and the entire neurocranium. But she is pleased to have been able to give the professor his face back. Her reconstruction resembles the portrait of Fomann during his tenure as a professor at the »Salana« university. She is quick to point out that his nose is narrower in the portrait. However, this may well be due to the painter’s artistic freedom.

This is where the written sources on Jena’s university history of the 16th and 17th centuries come into play, which are kept in the University Archives. They document the academic and scientific work of Fomann and other professors in the early modern period, who are now brought to life through facial reconstruction and portraits. Further information is provided by the records archived at the Thuringian State and University Library. This combination of basic archival sources and archaeological findings, scientific and medical examinations, restorations and presentations is exactly what this special project offers, says PD Dr Stefan Gerber, who is in charge of the University Archives. The project was initiated by his predecessor, Prof. Dr Joachim Bauer, who led the research into the »Collegium Jenense« for many years.

Ortolph Fomann the Younger now has a face again. But we are far from finding answers to all the questions we have for the professor and his contemporaries buried on the Kollegienhof grounds. As the project continues, more exciting findings are waiting on the horizon. A documentary series on the project is being produced for the regional broadcaster, MDR, with funding from the Thuringian State Chancellery. The first part will soon be available on the website made for the Kollegienhof project. One thing is certain: When the project is over, the bones will be returned to their original resting place.

Information about the project

In 2018, an interdisciplinary team of experts launched a project entitled »Jena’s Early University History based on the Collegium Jenense Grounds with a Special Focus on the Rectors’ Graves«. The aim is to present the unique ensemble around the former monastery grounds (»Kollegienhof«) in all its facets and to make it accessible to visitors—in both an analogue and digital setting. The project was initiated by Prof. Dr Joachim Bauer, who spent many years in charge of the University Archives, and his successor PD Dr Stefan Gerber. In addition to the three applicants (the University Archives, the Chair of Pre-History and Proto-History with Prof. Dr Peter Ettel and the Chair of Early Modern History with Prof. Dr Kim Siebenhüner), the project brings together other university partners such as the Institute of Art History and the University Hospital. Some of the non-university partners include the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, and the State Office of Monument Preservation and Archaeology of Saxony-Anhalt. The project is largely financed by the Ernst Abbe Foundation in Jena. The project marks a continuation of the research into the history of the University of Jena in the early modern period, which was intensified in 1998 in the run-up to the 450th anniversary of the »Hohe Schule«, which opened in 1548.